A day in the life of a midnight beam master

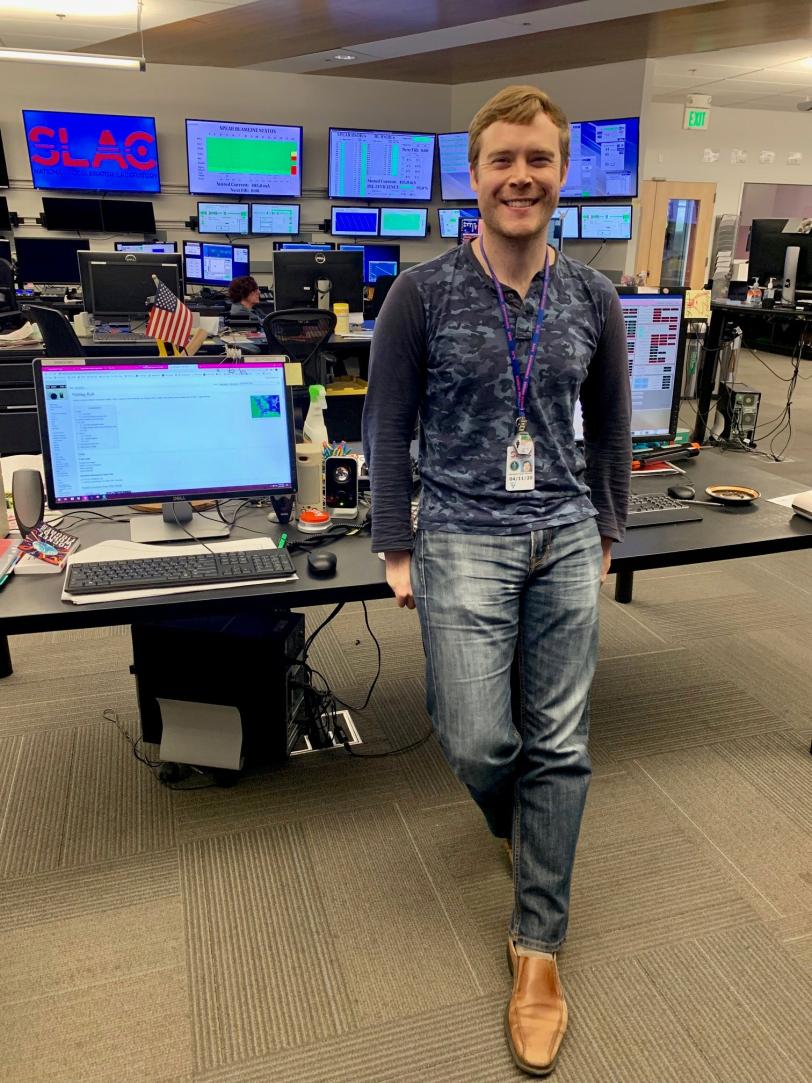

In SLAC’s accelerator control room, shift lead Ben Ripman and a team of operators fine-tune X-ray beams for science experiments around the clock.

When is a day not a day? When you work in the central nervous system of the world’s longest linear accelerator, open 24-7.

“There’s a constant cycle of people coming and going,” says Ben Ripman, an operations engineer at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

He might start at 8 a.m., at 4 p.m. or at midnight. But the shift rotations are no barrier to his passion for the job – leading a team of control room operators who deliver brilliant X-ray beams for scientific experiments.

Control room operators spend most of their workdays (or nights) in a room filled with monitors, three deep and crowded with numbers, charts and graphs. Those displays track the status of thousands of devices and systems in the linear accelerator that runs through a tunnel below Highway 280 and feeds SLAC’s X-ray laser, the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS). The accelerator boosts electrons to almost the speed of light and then wiggles them between magnets to generate X-rays. That X-ray light is formed into pulses and optimized for materials science, biology, chemistry, and physics experiments.

The entire operation is monitored in the control room, which also serves SPEAR3, the accelerator that produces X-rays for the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL). Another set of monitors, staffed by SLAC Facilities, tracks water, compressed air and electricity systems that serve the lab campus.

Ripman and his fellow operators are experts in reading these digital vital signs. But they are also some of the most knowledgeable people at the lab when it comes to the entire physical machine.

“We know the accelerator from beginning to end,” he says. “When an operator adjusts something from the control room, they can picture that machine part and what it is doing.”

For LCLS, they measure the amount of energy in individual X-ray pulses being fed to experimental hutches and often spend hours improving the pulses: tweaking magnets, adjusting the undulators, tuning the shape and length of the electron bunches.

Some days the control room is quiet, and the operators focus on training and individual projects. On other, more challenging days when the machine is running in exotic modes, they work elbow to elbow with physicists.

“We love this machine, but the accelerator was built decades ago and can be cantankerous,” Ripman explains. “When things do go wrong, it’s like a game of pickup sticks – one problem triggers another and you need to know how it all fits together.”

An important part of the job is knowing who to call for help. “We wake up a lot of people in the middle of the night,” Ripman says with a smile.

Control room operators also make sure everyone who goes into the accelerator tunnel stays safe.

There are two ways to get into the accelerator. For minor repairs and inspections, people take keys from special key banks that block the accelerator from turning on until all the keys have been returned. On official maintenance days, the doors are thrown open.

“On those days, maintenance crews, engineers and physicists descend into the tunnel and swarm the machine to resolve as many issues as possible before we have to summon them out again,” Ripman says. “We search the machine to make sure everyone is out before it’s turned back on.”

Almost all of the displays in the control room were designed by the operators, he says. “We are known to hide ‘Easter eggs’ in them, but you have to get in our good graces to find out about them.”

New operators take more than a year to get trained and proficient, Ripman says. “People come with a physics degree, but there is not a lot of formal coursework you can take on accelerator operations – it’s a lot of on-the-job training.”

It was that hands-on learning that drew him to the job in 2010.

“I was a nerd in high school,” Ripman admits proudly, “Stephen Hawking was my hero.” After studying physics and astronomy in college, Ripman worked as a contractor for NASA before joining SLAC. On his off hours, he plays board games and travels several times a year for card tournaments. He also loves hiking, skiing and snowboarding, and is a member of the Stanford University Singers.

His favorite thing about the job? “My coworkers,” he says. “I have the privilege of working with smart, fun, quirky people. We all get along quite well, and there’s a great camaraderie.”

Operators leave sticky notes with jokes or short messages for the next shift and share stories about their days and nights in the accelerator’s brain.

Like the one about a ghost calling from an abandoned tunnel. But that’s a tale for another night…

LCLS and SSRL are DOE Office of Science user facilities.

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.